ROLLAND, The Very Rev Sir Francis William Kt, CMG, OBE, MC, MA, DD (1878-1965). See Also

'The Geelong College 1861-1961' text for Chapter 8 on Sir Francis RollandSee Also

Outback Pioneer: Sir Francis Rolland and the Inland Nursing ServiceRead student memories of 'Mr Rolland' in the

Ad Astra December 2020.

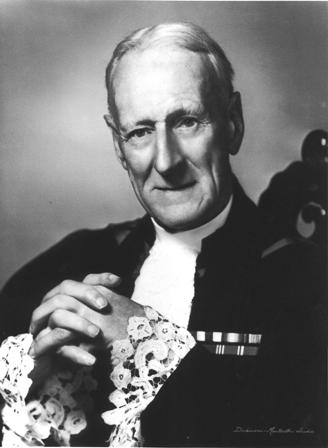

Very Rev Sir Francis Rolland

The following obituary was published in

Pegasus of June 1965:

'When Francis William Rolland was born at St George's Manse, Geelong, on June 12, 1878, he was already closely connected with the Geelong College. His grandfather, the Rev (later Dr) A J Campbell, the minister of St George's, was the original mover for the College's foundation and its strongest supporter in the difficult years which followed.

On a trip to New Zealand, Mr Campbell had recruited a young man to be his assistant at Geelong. That young man, William Stothert Rolland, though in his later twenties, became a student at the Geelong College in preparation for the ministry, and also became eventually Mr. Campbell's son-in-law and the father of Francis William. A few years later the Rev W S Rolland, as he then was, was called to Prahran, and his sons attended the now defunct Toorak College. Frank Rolland was a tall boy, good at his school work, as at tennis and cricket, a prefect at the Toorak school and a natural leader with a lively sense of fun. As he suffered a hesitancy in his speech, he studied elocution and on at least one occasion gave humorous recitations at the school break-up. From Toorak he went to Scotch College, then situated in East Melbourne, and when he left in 1895 he had gained his matriculation and played in the first football team.

He proceeded to the University of Melbourne and took the Master of Arts degree. He gained a Blue for tennis, in which sport he also represented Victoria in inter-state matches. After studying theology at Ormond College, he engaged in post-graduate studies in divinity at Edinburgh during the session 1904-5. Later, in 1905, he was ordained in Adelaide and appointed to the work of patrol padre in the Smith of Dunesk Mission, with his base at Beltana in the north of South Australia. His decision to ‘bury himself’ in the bush caused a ripple of surprise among those who knew him, but this was the moment of destiny for him and for many others. His three years with the Mission set the pattern for the rest of his life; from then on, he was always the missionary, always on the frontiers, refusing to see things as impossible because he or others had never done them before.

At Beltana, the young Mr Rolland cheerfully accepted very poor conditions, living in an earth-walled hut and travelling long distances between homesteads in a ‘buggy and pair’ under severe climatic conditions. The people often told him of others further out who should be visited, and he carried his work as far as the transport allowed, even to the point of serious risk. On several occasions he was lost and might well have perished but for the watchful care of those who admired and appreciated his work and also knew his almost childlike disregard of danger.

There were many ways in which the young missionary was not a ‘practical man’, but he was not all visionary either. He saw and was appalled at the lack of medical facilities in the vast area north of Port Augusta, and was practical enough to learn to draw teeth and to do minor surgery so that he could give some small immediate relief. Soon he began to campaign for the settlement of a nurse and, if possible, a hospital at Oodnadatta, which was then the northern terminus of the railway. In this he was strongly supported by his parents, both of whom were now influential Church leaders. But he was ahead of his time; the proposition was not yet practicable.

In 1908, Mr Rolland became parish minister at Noorat, Victoria, his only such charge, but his connection with the Inland was not broken. His opinion was still highly valued, and in 1910 the South Australian Assembly agreed to the erection at Oodnadatta of a hall, receiving ward and nurse's quarters, which was named the ‘Rolland Home’. When the Rev. John Flynn was making his first call for extended services to the Inland, before the foundation of the Australian Inland Mission, Mr Rolland's advice was sought on operating conditions in the remote areas of South Australia. In 1911, the Home Mission Committee asked that Mr. Rolland be freed for one year to go to Broome, in the north of Western Australia, where there had been no Presbyterian activity for some years. Mr. Rolland accepted the challenge and took up residence in a hovel on the beach among men of the pearling fleet, in order the better to see life from their angle. Again he won appreciation and admiration, towards which his ability to beat all comers at tennis also contributed. In the year, he established the Church's work effectively and a regular minister was able to take over.

He was still parish minister at Noorat, but this phase ended in 1915, when he enlisted as a chaplain in the AIF, in which he was attached to the Fourteenth Battalion. The sharing of men's lives clearly attracted him more than routine duties. With complete disregard of self, and to the embarrassment of his officers, he ministered to the men under fire in the front line, where no chaplain was supposed to be. From the men he received the title of ‘The Cocoa King’, while officially his courage and devotion led to being mentioned in despatches, and later to the award of the Military Cross. He remained ever after a hero to the men of the Fourteenth. It is significant for the years which followed that Mr Rolland at one stage placed before the authorities a scheme for non-military education in the Australian Army. Nothing resulted directly from this proposal.

In 1919, after the close of hostilities, Mr Rolland was in England when he received a cable from Australia asking him to take the headmastership of the Geelong College — a veritable bolt from the blue. The College was in a desperate plight, and a few members of the Council who knew all the facts had thought of a desperate remedy, the appointment of this unusual minister-missionary-chaplain who had no experience in education, who made his own rules and had consistently succeeded in his dealings with people over a wide range of situations. When the matter had been clarified, Mr. Rolland accepted. Still in England and somewhat alarmed at his brand-new role — but venturesome as ever — he was busy visiting Public Schools and investigating post-war educational problems. He had recently married, and at the beginning of 1920 Mr and Mrs Rolland came into residence at the College.' The 'Rolland Era' is well documented, particularly in 'The Pegasus' and the centenary history, 'The Geelong College 1861-1961'. It suffices here to quote part of the minute entered in 1965 on the books of the College Council: 'Sir Francis Rolland came to the College in 1920 when its fortunes were at the lowest ebb. Enrolments, finance, staff, scholarship, sport, school spirit - all were in a poor state. Sir Francis was not a qualified teacher, and many including himself, had doubts about the probability of his success in such a difficult situation. But by patience and perseverence he led boys to see something of his own idealism; he gradually assembled an effective teaching staff; he won influential and active friends on the Council and among the public; he reawakened the enthusiasm and pride of Old Collegians. By the late 'twenties confidence had returned, and a vast building programme was undertaken. Higher standards in traditional scholarship and sport earned respect for the College, while new concepts like the House of Guilds and the House of Music broadened the scope of its work among boys of varied talents. Even after Sir Francis retired as Principal in 1945, his influence continued to be felt in the completion of the main quadrangle and cloister and the establishment of the new Preparatory School, both of which he had envisaged'.

'Mr Rolland's work received wide public recognition while he was still at the College. In 1936-37 he was Moderator of the Presbyterian Church of Victoria, and from 1936 to 1939 Chairman of the Headmaster's Conference of Australia. In the earlier years of World War II he undertook two overseas missions for the Commonwealth Government. His school duties, in which the Principal did not have the assistance now available, the added outside responsibilities and the strains of wartime made up a heavy load. He often seemed tired, and he spoke of the loneliness of a headmaster. He had been asking the Council to release him, and at last his resignation was accepted in 1945, when he was past retiring age.

Before long Mr Rolland was again hard at work. ... He was largely responsible for reorganizing the training of deaconesses in Victoria; he played a leading part in a drive for better religious instruction in State Schools; he was one of those whose work led to the introduction in 1965 of Biblical Studies as a subject of the Intermediate Certificate examination; he undertook several emergency tasks for the Church.

In 1954, he was appointed Moderator-General of the Presbyterian Church of Australia, the highest office of the Church, involving a three-year job of work, which he carried off with characteristic zest and distinction. Many other honours came to him: triple royal recognition culminated in the knighthood which was conferred in 1958 for ‘distinguished services in war and peace ’, the first such award to a clergyman in Australia; in 1960 the University of Edinburgh bestowed upon him the degree of Doctor of Divinity, welcoming the opportunity to honour a man who had become ‘a legend in his own life-time’ .

After Sir Francis retired from his formal positions, the Rolland lived at 8 Toorak Rd, Camberwell South (1949, 1954)and later at a smaller house at 26 Nott St, East Malvern (1963). The Very Reverend Sir Francis William Rolland, Kt., CMG, OBE, MC, MA, DD, Principal of the Geelong College from 1920 to 1945, died at Melbourne on January 22, 1965 after a short illness. The funeral service at Scots Church, Melbourne, on January 26 was attended by a large congregation.' He was cremated on 26 January, 1965 with a memorial at Springvale Botanical Cemetery, Melalleuca Section, Wall K, Niche 53. His wife, Enid Aline Rolland died on 25 July, 1964 after several months illness and was cremated on 28 July, 1964. Aline was similarly memorialized at Springvale, Melaleuca Section, Wall K, Niche 57.

Sir Francis Rolland is memorialized in the naming of several features of the College including the

ROLLAND CENTRE at Senior School, and the

ROLLAND WINDOW in the Chapel. His portrait by

Arthur Wheeler hangs in the Senior School Dining Room.

TO ROLLAND OF GEELONG

Perhaps the desert spaces strengthened vision

In former days, or searching farther seas

Confirmed a northern heritage of dreaming

Which never sought its peace in leisured ease;

Be as it may: these sunlit acres cherish

The grace of years, the dignity of toil,

And future generations reap the harvest—

Triumphant verdure sprung from arid soil.

When, in this continent, we find salvation

From lethargy, and face with eager heart

Her splendid challenge to a fearless nation,

In your example some will find their part

Nobly you captained in the fields of youth,

Your weapons, beauty, and your armour, truth.

Anon. ('The Pegasus', Dec., 1945)

Wiki.JPG)

College Principal, Francis Rolland.

A second more personal study of Rolland's character was also published in

Pegasus of June, 1965.

'Tall, well above six feet, ascetically slim, yet good-looking, Mr. Rolland cut an imposing figure in any company. His hair was short, straight and brownish, becoming snowy white as he grew older. His gentle, but ever alert, grey-blue eyes seemed to twinkle, revealing the deception in his almost lazy physical movements, the uncoiling as he stood up, the springy, floating gait. His aquiline nose and concentrated gaze would have suited the traditional detective. His hands were often in rhythmical movement like those of a dancer; some would have said a musician's hands.

His voice was rather light; he must have been a tenor, though he seldom was heard to sing; his accent was cultured, with pure vowels and a slight drawl. Sometimes there came a recurrence of the boyhood splutter in his speech when, under excitement, his tongue could not keep up with his racing thoughts. In anger, which was very rare, his eyes seemed to flash sparks, he groped for words (politely damning) which burst forth in a cry of prophetic despair rather than a shout.

However, his normal mood was that of easy, slow-moving, slightly-smiling restraint, a sphinx-like inscrutability, with the minimum of words, almost as though he had forgotten to say something. Some people found him hard to talk to: his softly spoken, subtle, staccato comments were often difficult to keep up with, or to answer, when he turned the conversation into a fencing bout. At other times, socially, he spoke freely enough, but preferred whimsical comment to any discussion of his own feelings. When something really amused him, he would throw his head back in a paroxysm of gentle laughter.

By contrast, his formal public utterances, which were usually prepared with great care, were pronounced in his thinly ringing voice with incisiveness and authority. His sermons and addresses were enriched from his wisdom and wide experience, and he was always liable to introduce touches of epigrammatic humour calculated to startle his listeners to attention. ‘A headmaster's work consists mainly of interruptions to it.’ ‘Headmasters may be a terror to evil-doers, but evil-doers are far more of a terror to them.’ Opening a lecture on Central Australia, he once announced: ‘I want to talk to you about your inside.’ He told a speech-day audience that he had known a headmaster who thought 'his boys a bad lot until he met their parents’, but denied that this was his own experience.

Most people thus tend to think of Mr Rolland with a feeling of innocent fun, further heightened by the memory of his notorious absent-mindedness, which he himself enjoyed. It was his custom to rehearse a prefect in the reading of the Bible lesson for morning assembly. (The appointment of prefects is the headmaster's prerogative.) One day Mr. Rolland saw a boy, not a prefect, outside his office, took him in and put him through the lesson. Having qualified, the involuntary impostor went and told the prefect that he need not keep his appointment. On another occasion, it is said, Mr Rolland was seen knocking at the door of his own office.

It might be said that Mr Rolland was not a good teacher. Indeed his lack of the required training caused some strain at first with the education authorities and with certain conservative members of his staff. In matters of detail, he did not pretend to be a business man either. This successful management came from his attention to the long view and the broad canvas, combined with a single-minded devotion to the job in hand.

His first battles at the College were concerned with finance and property, on the grand scale. When he took office there was a heavy debt, and members of Council seemed content that the Church was willing to make loans, although these added to the burden of interest. No progress could be made under such conditions. Mr. Rolland demanded that the rot be stopped and that Old Collegians be persuaded to put the College on a sound footing by voluntary giving. He was prepared to resign over this point, and, of course, he had his way. On the question of moving the College out of town he made a compromise. From the first he had marked down the site overlooking Queen's Park, and after forty years his ambitions were realized in part. But when it was clear that the old site would be retained, his genius was employed, especially in the years 1927-39, in remodelling the property, not only in bricks and mortar, but also in beauty and dignity. Mr Rolland's tact, sincerity and gentle-manly bearing gave him and his College a standing in the community which it had lacked for many years. He was able to persuade a number of generous individuals of the tightness and soundness of his schemes and thus to win their personal and financial support.

He had strong views on the attitudes of Old Boys, especially those who made adverse comparisons with the ‘good old days’, paid lip-service to the College, and did nothing to support it actively. He insisted that looking back to the past is one thing, but wanting to go back is another. He valued the positive assistance of the OGCA and, after 1945, enjoyed being an honorary life member and meeting fraternally with his fellow members, most of whom had been his pupils.

.jpg)

Rev Francis Rolland in his office, Geelong College, 1945.

He was always strongly for the ‘under dog’. In 1921, he revealed his hope of having masters set aside for the teaching and encouragement of boys who were handicapped by absence, ill health or mere slowness. His zeal in later years for craft work and hobbies, holiday adventure, music, physical education and cadet training was an attempt to offer something for everybody, so that a boy who might previously have been dubbed ‘useless’ could gain respect and self-respect through his own peculiar excellence.

It is true that Mr Rolland often had no time for little mechanical details. He expected his staff to cope with these, and stated that it was a headmaster's job to see that things were done, but not to do them. In a loose interpretation, this sometimes meant that assistant teachers were left to their own devices; for better, when they fought their lonely battles and won; for worse, when they gave up in despair and resigned. There emerged in the long run, by this form of natural selection, a staff of men independent in their own departments and loyal to the general plan of campaign.

In one area, however, Mr. Rolland was intensely, even fiercely, concerned with trifles. This was in his person-to-person relations with the individual, from the visiting dignitary to the newest junior boy. He was an expert fisher of men. His absent-mindedness vanished, he remembered names clearly, his wit, wisdom, intelligence and good humour, his sporting ability, were brought to bear as seemed expedient to reach the objective. When he was playing ‘catching’ with a group of little boys, or taking part in a game of chess, none was keener than he; none en¬joyed it more. In such moments he lacked entirely the self-consciousness of the regular class teacher; he was himself openly a boy. When he ‘gave’ a six-year-old one of the trees bordering the Mackie Oval, he made a friend for life. He asked another boy for his orange — and took it! A few days later that boy and his mates received a case of oranges, which had to be cleanly caught before they could be claimed. A senior boy was asked to leave for breaches of discipline; during the next vacation he was taken on an extended tour. Another was seriously depressed, feeling that he had let the College down in an important match; he was sent away for a couple of days and advised to visit the zoo, where he would see creatures worse off than he. There was more guile in the sudden rise of the poorest scholar of a class to first place in the Scripture examination. A special aspect of this shock treatment was the wish to keep the College from growing too big, so that there could be a family atmosphere, each knowing all, and so that its members must always fight hard in outside competition, even to win occasionally. At first this may have been making a virtue of necessity, but the attitude was justified by its results and maintained to the end.

Mr Rolland grew old in years, yet he refused to be old. In 1963, when the College was to play in the Public Schools football final, he wrote the captain a letter of exhortation, stressing that the result might depend on ‘the individual will power of each weary player in the fourth quarter’—a magnificent parable of life as he lived it. In 1964, he was closely interested in the Old Collegians' new ideas for supporting College finances, and his last letter to the College expressed ‘my best wishes ... to the Old Collegians and my congratulations on their long-distance vision’.

Did this maker and leader of men have some special resources, or is his greatness an open secret? He certainly was wise by nature and nurture. He was cultured, learned, a master of the English language. But ability and dignity were merely the outward expression of inward serenity based on an assurance of his high calling and the possession of strength to fulfil it.

His visible, personal religion was a balanced combination of mysticism and vigour, and, appropriately, ‘Jerusalem’ became one of the College's great hymns. Like Christ, he was a revolutionary, his love of people and his eagerness to push on with his work far outweighing any attachment to Pharisaical forms and pretensions. Sometimes there were hints of inward struggle—‘Lord, I believe; help thou mine unbelief’—yet while Mr Rolland may have felt that he failed in details, he passed handsomely the tests for entry into the Kingdom of God. Putting his hand to the plough, he never looked back; he possessed the faith that moves mountains; he busied himself in ministering, without thought of receiving ministrations.

Mr Rolland will be always honoured at Geelong. He was not the first great man to work here, but he ensured also that he would not be the last. His spirit will endure in the lives of those who have been and are still to be influenced by his example of faith and good works.'

'I hate everything that in a School gives the air of a gaol or an asylum. It is my chief aim to make the College less institutional and more human'. – Rev F W Rolland, 1935.

Sources: Pegasus June 1965 pp 11-14; 'The lives of Frank Rolland' by B R Keith. Adelaide: Rigby, 1977; 'Rolland, Sir Francis William (1878 - 1965)' by B R Keith, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 11, Melbourne University Press, 1988, pp 444-446.; 'Fathers and Brethren: The Moderators of the Presbyterian Church of Australia, 1901-1977' by Malcolm D Prentis. Church Heritage, 12,2 (Sept 2001) p 136.